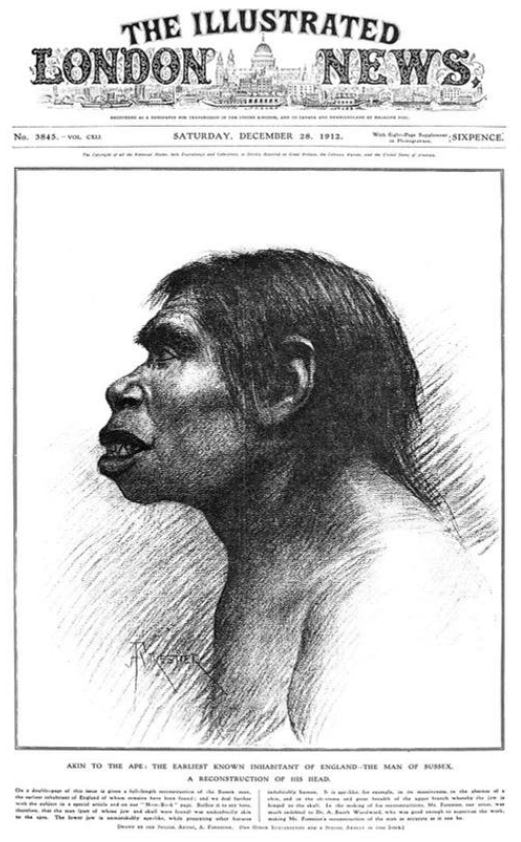

The “Piltdown Case” relates to an English hoax or joke in which someone at Piltdown in Sussex buried an unusual human skull (stained brown) with a modified orangutan jaw (also stained brown), to look as if the relatively modern specimens represented a fossilised “ape-man”, apparently associated with the fossilised bones and teeth of animals known to have existed more than a million years ago. This Piltdown Man “fossil” was discovered in 1912, and announced with much acclaim at the end of the year in London as Eoanthropus, the “Dawn Man”, otherwise referred to as “The Earliest Englishman”. Many people have been suspected as fraudsters, especially Charles Dawson, an amateur archaeologist who lived near the site of Piltdown, but more than a century later the case is still not closed. In addition to Dawson I have been interested in the possible role of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French palaeontologist, Jesuit priest and philosopher who had taken part in excavations at Piltdown in 1912, and who had visited the site again the following year, when he picked up an isolated orangutan canine tooth. De Chardin had discovered the specimen in an area which had already been thoroughly searched, which has raised suspicion. I am not claiming that De Chardin was the “principal perpetrator”, but he does deserve attention. In particular, one may ask whether he was aware of a joke in which he was an accomplice. Evidently something had gone wrong with the hoax in 1912 after it was taken seriously by Smith Woodward, the head of the geology division at the Natural History Museum in London. In the South African Journal of Science and in Evolutionary Anthropology I have presented a scenario in which De Chardin knew that a certain Edgar Willett was the main perpetrator. Willett was a retired medical man, trained in Oxford. He had been a curator of a museum at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, had a knowledge of anatomy and had access to unusual human skulls. In early retirement he lived near Piltdown. Notably, he had assisted with excavations at the Piltdown site in 1912. By 1913 he had apparently become a member of an “inner circle”. After a period when no fossils had been found, the orangutan canine was picked up by De Chardin on 30 August 1913. Perhaps not coincidentally, it was the very day when he joined the excavation that year. Of particular interest is the source of the tooth. In 2016 Isabelle de Groote, Chris Stringer and their colleagues were able to demonstrate from DNA that it must have come from the Sarawak region of Borneo. An expedition to that area was undertaken by Alfred Everett in 1875, sponsored by, among others, Charles Darwin and three members of the Willett family, including Edgar and his father Henry (Sherratt, 2002). The expedition brought back orangutan material, most of which went to The Natural History Museum (BMNH), but it had been agreed in advance that “duplicates” could go to collectors. It would seem entirely probable that such “duplicates” would go to sponsors of the expedition. Tom Harrisson (curator of the Sarawak Museum) informed Kenneth Oakley (at The Natural History Museum) that some orangutan specimens collected by Everett would have gone to “dealers” (De Vries, H and Oakley, KP, 1959). Thereafter such material would have been distributed to private collectors. This brings us to the question as to whether Willett was the “collector” to whom De Chardin referred in correspondence with Henri Breuil (IPH Institute of Human Palaeontology, Paris) and Oakley. As someone who claimed that he knew the identity of the principal perpetrator, and as a priest whose honesty would be expected to have been unquestionable, De Chardin was most certainly suggesting to Breuil and Oakley that a collector other than Dawson had planted ape material in the Piltdown pit. Remarkably, in an essay on human evolution published in January 1913 in the Jesuit journal Études, De Chardin wrote that: “There was a time when prehistory deserved to be suspect and the subject of jokes.” Even more remarkable is the fact that De Chardin makes no reference to Piltdown Man in the essay, even though the “fossil” had just been announced. In 1920 De Chardin wrote his only publication on Piltdown, in which he mentions that the condyle of the orangutan jaw was broken “as if on purpose”. Without this critical condyle, it would not have been immediately obvious that the ape jaw did not articulate with a human skull. In 1920, nobody at the time had as yet suspected a forgery, but in this short phrase (“broken as if on purpose”) we see the hint of a hoax. Stephen Jay Gould considered this as a smoking gun, indicating De Chardin’s singlehanded complicity. I do not go so far. Instead I consider that Piltdown Man was intended as a simple joke that went wrong, too quickly, involving at least three people: Willett principally, aided by De Chardin and Martin Hinton who is known to have stained bones experimentally at The Natural History Museum. I suggest that the motive was to hoist the ambitious Dawson (a serial fraudster) on his own petard. At least potentially, Willett had access to the necessary materials, including unusual human skulls (from the museum which he had curated in London), orangutan jaws and teeth (from Borneo), and fossils of a diversity of animals (from his father’s extensive antiquarian collections in Brighton). The wealthy Willett in early retirement had the means, had free time on his hands and the necessary background in anatomy from Oxford. De Chardin had a basic understanding of palaeoanthropology. Hinton contributed his experience from experimenting with the chemical staining of bones. I regard them all as suspects, with Willett having been the orchestrator. In New York in 1914, William King Gregory wrote the following with regard to Piltdown “fossils” (published in The American Museum Journal, 14:189-200): "It has been suspected by some that geologically they are not old at all; that they may even represent a deliberate hoax, a Negro or Australian skull and an ape jaw artificially fossilised and 'planted' in the gravel-bed to fool scientists". From whom did he get this rumour? I propose that it was none other than Teilhard De Chardin. The two of them had met during a dinner with Smith Woodward in London in 1913. Just imagine them having a discussion about Piltdown, after more than one glass of wine. Teilhard might have jokingly seized the opportunity to tell Gregory the truth about the joke, but to pass it off as a rumour he had heard (without implicating himself), in the hope that this “rumour” would be taken seriously, helping to expose the hoax. That's my scenario. Teilhard was a joker. And it has been said that at that time, Jesuits were allowed to lie, providing it was a joke (Thackeray, 2012). Acknowledgements: I am grateful to the Trustees of The Natural History Museum for the opportunity to examine archives relating to Piltdown. I am also grateful to the Teilhard de Chardin Foundation and the Jesuit Archives in Paris for access to material in their care. Stephen Jay Gould enthusiastically encouraged me to pursue the Piltdown Case. I have enjoyed animated discussions with Chris Stringer and Chris Dean, and correspondence with Martin Pickford. This item for Palaeo-Palaver is primarily an extract of an article that appeared in the Mail and Guardian in February, 2022. References: Thackeray, J.F.2012. Deceiver, joker or innocent? Teilhard de Chardin and Piltdown Man. Antiquity 86:228-234. Thackeray, J.F. 2019. Teilhard de Chardin, human evolution and “Piltdown Man”. Evolutionary Anthropology 28: 126-132. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21773

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Palaeontological Society of Southern AfricaPalaeoShwe art by Sciism & Puppet Planet © 2022

|

Contact us here: |